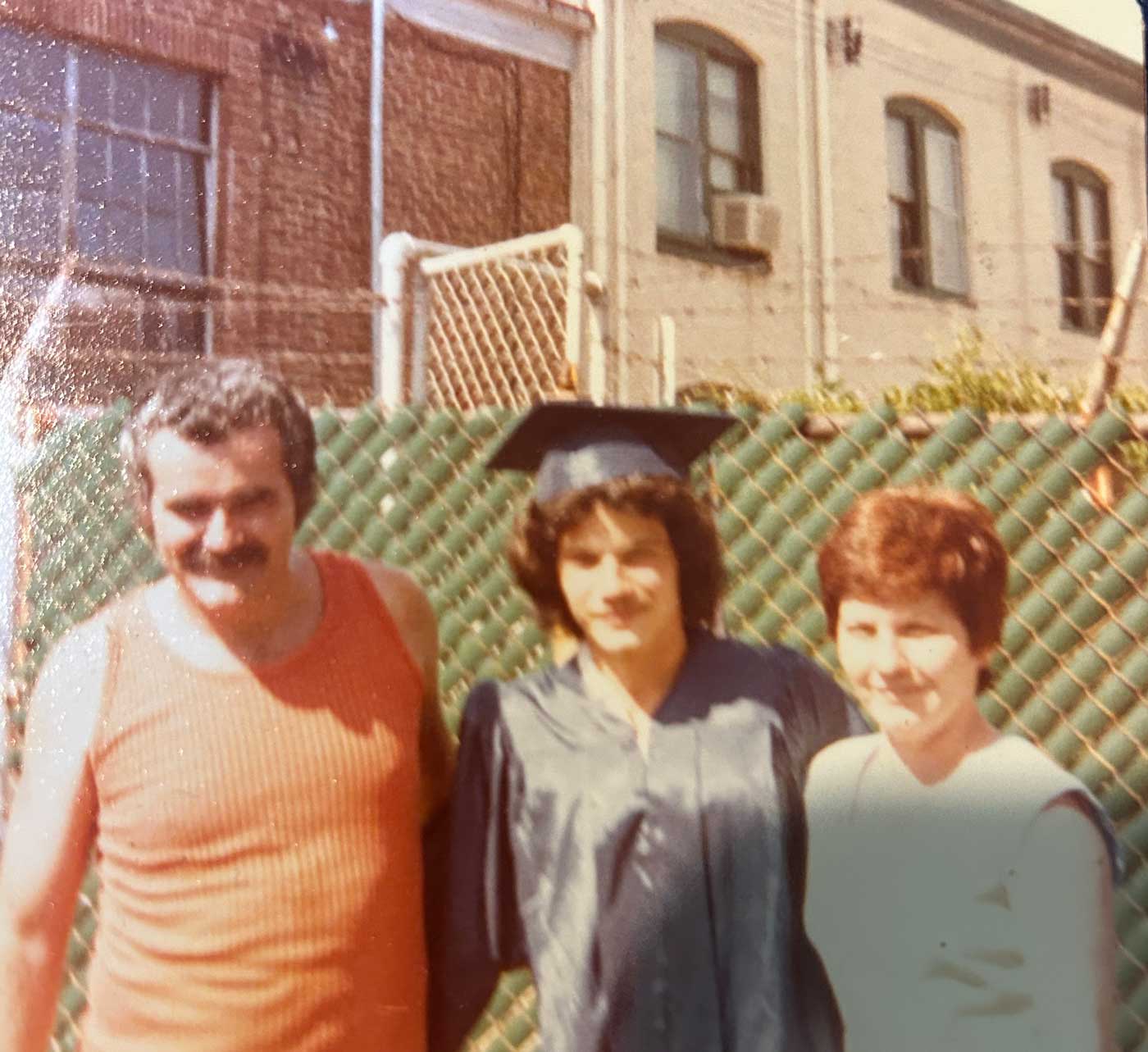

Bobby Suny at his graduation from Darby-Colwyn High School in 1978 with parents Jim and Marilyn Dougherty. Bobby would be fatally shot in July the following year at barely 19 years old.

All photos in this article provided courtesy of Bobby Suny’s family.

Bobby’s Story

By Rose Quinn

Published in the Delaware County Daily Times on May 31, 2024

Robert “Bobby” Suny had the hair of a “king.”

He was about 4 when a lousy cold landed him in the hospital. Soon into Bobby’s nearly weeklong stay, Marilyn Suny Dougherty began hearing nurses remark about her son’s thick, dark mane.

“They called him Elvis,” Marilyn recalled with a faint smile.

Bobby got over his cold, but the nickname stuck.

“Bobby did love his hair, and as he got older, he liked wearing it long, not the buzz cut he would get every year before (elementary and middle) school started,” his mother said. “His hair was beautiful.”

Bobby was an athlete, a Boy Scout, and a motorhead.

He was also an artist, a deep thinker, and a teenage romantic. He loved music, comic books, animals, and his circle of friends and family.

At 87, Marilyn has lived half of her life with only memories of her first-born son, slain nearly 45 years ago. Bobby would be celebrating his 64th birthday on May 31.

“I miss him every day,” she said.

Bobby was barely 19 on July 12, 1979, when a discharge from a long rifle cut short his busy, happy life, without any provocation or mercy.

The single .22-caliber round pierced his chest as he was walking along railroad tracks, a shortcut home to Darby from a Catholic church carnival in southwest Philadelphia.

According to authorities, that familiar — and final — path led Bobby into the sight of a group of youth drinking and doing drugs in the dark, isolated area. One of them was armed.

Marilyn Suny Dougherty was recently at her son’s grave. “I’ve been heartbroken since the day he died,” she says.

Treasure-trove of memories

When Bobby’s body was found near the B&O tracks at Third and Fern streets, he was maybe three blocks and about as many walking minutes away from his family’s Columbia Avenue twin, their home in Delaware County for about two years.

Echoing decades-old Darby police and other published accounts, Bobby’s mother and siblings said that after Bobby dropped to the ground, some in a group then dragged his mortally wounded body — all 5 feet 7 inches, 135 pounds of him — some 50 to 60 feet onto the tracks, seemingly hoping the next passing train would cover up the shooting.

Bobby somehow managed to crawl off the tracks.

Early investigators believe Bobby was dead when a train sped by, and the conductor stopped and called police, according to Darby Police Chief Joseph Gabe, citing previous reports.

“It’s been a nightmare,” Marilyn said recently. “It’s heartbreaking when you lose a child. I don’t care who you are, unless you are a cold person. I’ve been heartbroken since the day he died.”

Today, what torments Marilyn almost as much as she misses her son is that although police zeroed in on a suspect decades ago, they still lack enough evidence to file murder charges against him.

The suspect, whose name is being withheld, served time in prison for manslaughter and weapons offenses in a case years after and unrelated to Bobby, and has long been a free man.

“We always hope for a tip or a break in any cold case. I would like to bring some sort of closure and justice for the Suny family,” Gabe said. “In a small town like this, somebody knows.”

Over the years, a few seemingly solid leads fizzled out, and some witnesses died.

“There is no statute of limitations for murder,” reminded Gabe.

Marilyn Suny Dougherty and all five kids with Bobby in front.

Sometimes, the haunting “what ifs” latch onto Bobby’s mother and siblings as if no time has passed.

The Phillies played at Veterans Stadium that fateful Thursday night, defeating the San Diego Padres 4-3. It was the first time Bobby had missed a home game since his blue-collar family began working concessions for fun and added income.

“He never took off, but that night, he did,” Marilyn said. “He wanted to go to the carnival.”

Barbara Suny Higgins thinks about her SEPTA TransPass that she offered her brother to use before he left for the carnival.

Instead, he opted to ride his bicycle. When it was time to leave the fairgrounds at the Church of the Good Shepherd, Bobby lent his bike to a friend who lived farther away than he did.

“That was just like him to do, too,” Marilyn said. “He cared about other people.”

Those were the last conversations Marilyn and Barbara had with Bobby.

“That carnival was a big deal,” said Barbara, adding she overhead Bobby talking about it with his girlfriend earlier that day.

“Everything in our lives changed that night,” said Diane Dougherty O’Hara, the youngest of the five siblings who was 14 when Bobby was murdered.

With a shelf that Bobby made for his mother are, from left, sister Barbara Suny Higgins, mom Marilyn Suny Dougherty, sister Diane Dougherty O’Hara and sister Kim Suny O’Hanlon.

Bobby’s family is a big, close bunch.

Like their mother, sisters Barbara, 66, of Sewell, New Jersey; Diane, 58, of North Wildwood, New Jersey; Kim Suny O’Hanlon, 67, of Springfield, with whom Marilyn makes her home; and brother, Larry Suny, 61, of Collingdale, carry him always in their hearts.

As the years pass and their family continues to grow, they never stop talking about Bobby, including him in spirit at holidays and other celebrations from minor to milestones the best they can.

“I relive my memories all the time. I don’t want to forget him,” said Kim, with Marilyn and both sisters all nodding in agreement.

Sitting around Marilyn’s dining room table in her in-law suite, tears and laughter flowed for hours as the women reminisced.

From one to the next, they passed photographs pulled from old albums and other precious treasures. Among the trove: Bobby’s baptismal certificate; his high school diploma; a wooden shelf he made in a vo-tech class for his mother; two 1969 certificates for good dental health; an old flannel shirt, which, along with jeans and construction boots, was his go-to attire; and his high school ring.

Bobby lost the ring shortly after he got it but never told anyone.

It was more than a welcome surprise when a woman who found it along Cobbs Creek Parkway, where Bobby often congregated with friends, returned the ring to the family about a decade after his death.

His sisters took turns wearing the oversized trinket with the royal blue sapphire stone.

Bobby’s hands were like magic, whether carving wood, fixing a car, or drawing.

“My brother was an incredible artist. His freehand was unbelievable,” Larry said in a lengthy and emotional telephone interview.

He recalled that an art teacher was so impressed she even came to the house when Bobby was in eighth or ninth grade to talk about his abilities.

He remembers his brother as quiet but strong, “just the opposite of me,” he said. “He was my hero.”

Until Bobby’s later teen years, the brothers were always together. In addition to sports, they shared a love of music. They had mutual friends. They shared a bunk bed for many years, Larry on the bottom and Bobby on the top.

Like brothers, they had their blowups, but never for long.

“I talk to God. I tell him that he took the wrong brother,” Larry said.

Recalling Bobby’s sensitive side, Kim said he was around 12 and brought home a turtle.

“He named it Tumac the Turtle. Everywhere Bobby went, so went the turtle,” Kim said.

It was a similar scenario when Bobby and Larry brought home a dog they found in Mount Moriah Cemetery, which they named Munchkin.

Over the years, Bobby also had a cat named Smokey, a guinea pig named Arnold and a parakeet named Pete.

A family joke was that Bobby would never come right out and laugh.

“He was always quick to get a joke, but he would hold in laughing until his shoulders would shake,” Diane said.

The sisters laughed when their mother mentioned how much Bobby loved sardines.

“He ate them out of the can,” Marilyn said, adding, “with mustard.”

Barbara said sneaking a sip of his favorite Frank’s Black Cherry Wishniak soda would easily set off Bobby’s phobia for germs, which his mom and sisters agreed was off the charts.

“If you took a sip of Bobby’s soda, it was your soda,” Barbara said. “And at Halloween, his candy was his candy.”

Bobby loved Christmas, but he loathed decorating the tree.

He was afraid of horror movies and never watched one without a pillow covering his eyes. He avoided having his picture taken at every turn, or at least tried.

When the family had posed outside for a photo marking his eighth-grade graduation, Marilyn said, “He already changed, but we made him put his suit back on for the picture.”

She’s grateful now for every captured moment.

Brothers-in-law Mike O’Hanlon and John “Chet” Higgins had known Bobby since he was a kid.

As their age gap narrowed with time, they both believed Bobby would have become a close buddy.

“He missed a whole life,” Mike said. “In my head, he’s still 19.”

Happy baby, average student

Robert Frank Suny weighed about 7 pounds when he was born on May 31, 1960, at Preston Retreat Hospital, a private facility recommended to Marilyn by friends.

At the time, Bobby’s parents lived at 52nd Street and Baltimore Avenue in West Philadelphia, but Marilyn and Robert Suny Sr. would separate not long after he arrived home. Bobby never used the junior suffix.

“To me, it was exciting to have a son,” Marilyn said. “He was a good, easygoing baby.”

Bobby was 3 when Marilyn moved the family to Wilton Street, and later Salford Street, in Southwest Philadelphia. By then, Marilyn had married James Dougherty, an old neighbor and brother of one of her girlfriends. He blended seamlessly into the family.

“He was a big part of all the kids’ lives,” Marilyn said of James, an Air Force veteran and retired ironworker. His death eight years ago left another tremendous void in the family.

Bypassing kindergarten, Bobby attended Mitchell Elementary School from first through sixth grades. He attended Tilden Middle School for seventh and eighth grades and Bartram High School for ninth, 10th and part of 11th grade.

In the spring of 1977, when his family moved to 626 Columbia Ave. in Darby, Bobby transferred to Darby-Colwyn High School for the remainder of his junior year and graduated with the Class of 1978.

Bobby was an average student, and his talent for woodworking emerged in vo-tech courses, Marilyn said.

Another nickname for Bobby was “professor,” said Diane, because he was so studious and quiet.

“The only way you knew he was coming down the steps or into the room was because his ankles cracked when he walked,” she said.

Why they cracked was a mystery.

Bobby Suny, left, at his baptism and confirmation in 1977 with his sponsor Chet Higgins.

Having her kids baptized was one of the first things Marilyn planned after her second marriage was blessed in the church.

Bobby was 17 when he, Kim, Barbara, and Larry were baptized and confirmed on April 18, 1977, at Most Blessed Sacrament Roman Catholic Church, their old parish in Philly.

Bobby picked Chet, Barbara’s then-boyfriend, to be his confirmation sponsor.

Bobby was proud of his Irish Catholic roots. Though he didn’t talk about it much, he was also proud of his Armenian heritage and had a special bond with his paternal grandfather, Souren Suny, family members said.

Bobby liked all sports. He played soccer for teams at Tilden and Darby-Colwyn. Marilyn, a stay-at-home mom, enjoyed attending his games.

“He was very athletic, and he took every game to heart,” Diane said. “When he lost, he didn’t talk to anyone. Not because he was a sore loser. He just cared.”

Bobby also played baseball and softball and ran track. But he especially liked street hockey, a passion fueled by the Philadelphia Flyers, especially the rough play in 1972-73 that dubbed them the Broad Street Bullies.

“We played a lot of hockey on Edgewood Street (in Philadelphia) because of the Flyers. We were all fans but couldn’t afford to go to any of the games,” Billy Everly, 62, a self-employed painting contractor, said.

Everly recalled that in May 1974, when the Flyers won the Stanley Cup, the first of back-to-back championships for the invigorated underdogs, they were among the revelers gathered at 60th Street and Chester Avenue that jubilant afternoon.

“When the game was over, everyone came out on the street and partied,” he said. “People were climbing on trolley cars.”

Bonds of friendship, young love

Billy, the Suny brothers, and Jimmy Kelly were the core of a larger group of friends.

“We were like a pack. We pretty much did everything together,” said Jimmy, 62, a Philly fire captain who grew up on Salford, a few houses away from Bobby.

Jimmy recalled that the nearby sprawling Mount Moriah Cemetery was like their playground, but they were always mindful of the reverent space.

“We had our little football field there,” Jimmy said.

They’d sled for hours on the hills beyond the graves on snow days.

On their most mischievous days, Jimmy said they’d slip into the cemetery after dark and play a game they named “let’s go get a chase,” in which they led the guard and his dog, a German shepherd named Laddie, on a wild goose chase, as they would all hide in the wooded area.

In daylight, they would always stop to talk to the guard, who never caught on to their mischief-making.

“We were young,” Jimmy said. “It was harmless fun.”

Not unlike pulling the plug on a fire hydrant on a neighborhood street to cool off on hot summer days, according to Billy.

“Nobody had a pool,” Billy said.

Many hours amongst the friends were also spent car slot racing.

“Bobby was kind of the leader of the group,” Jimmy said. “He was the oldest. He was the first to have a car and drive us all around.”

At a time when his friends turned their noses up at soccer, Bobby not only got them to play, but like it.

Larry Schad was one of them.

“I played at Bartram High School after he introduced me, went to Philadelphia Fury (pro soccer) games, later became a youth soccer coach, and played until I was 47,” Schad said in correspondence from his home in Florida.

Softball was another popular pastime, recalled Schad.

Schad said if they were not playing sports, they were talking music.

Some of Bobby’s favorites: Rod Stewart, Bruce Springsteen, Genesis, Bad Company, Bob Seger, Black Sabbath, George Thorogood and Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow.

According to his friends, Bobby was always fun but laid back. He would drink a few beers but never overindulge. Bobby was into physical fitness and built a weight bench.

He was motivated and more mature than most his age.

“I’m not saying he was an angel, but Bobby was not a person who went looking for trouble,” Jimmy said. “But he wasn’t afraid to stand up for himself, either.”

The trio of friends agreed Bobby was popular with the girls, but only one stole his heart.

Lori Lennox Caywood, 62, was friends with Bobby before they became a couple. They met through her best friend and Bobby’s cousin, whose father owned a gas station in Upper Darby where Bobby worked after high school.

“We would go there just to see Bobby,” Lori said.

She was attracted to his good looks and, later, his humor.

“There was something really special about him. Everybody loved him,” Lori, a happily married mother of two grown children, said in a sometimes emotional phone conversation. “He never got mad … we laughed all the time. He was just a good guy.”

Lori was so crushed by Bobby’s sudden death that her mother suggested she start journaling to help sort her feelings. Her first entry was Sept. 30, 1979, and her last was May 10, 1983.

Lori Lennox with Bobby Suny at the Upper Darby High School senior prom in 1979.

Lori’s recent rereading of the journals brought her to tears.

“I wrote things like I was talking to him,” Lori said.

“It was just hell the way it happened, just horrible,” she said of Bobby’s death.

Just weeks earlier, Bobby had escorted her to her senior prom at Upper Darby High School.

Dating for about a year, Lori and Bobby shared their hopes and dreams, long drives in his station wagon, trips to Phillies games, and time with family.

They enjoyed parties with friends and alone time when they dog-sat for Kim and Mike, newlyweds at the time.

Bobby often surprised Lori with yellow roses, which he pulled from his mother’s garden. On her 17th birthday, Bobby gave her a heart pendant, which Lori still has tucked away in a box.

“He was as romantic as a 19-year-old could be,” Lori said.

Lori remembers talking to Bobby about the carnival that Thursday afternoon, but she did not go with him or meet him there.

“I told him to have a good time and I would talk to him later,” she said.

Later, Lori got a call from Larry.

“I think Bobby is dead,” he blurted.

“I was just a mess,” recalled Lori. “The next day, Bobby’s death was on the news.”

Bobby Suny with family at his graduation from Darby-Colwyn High School in 1978

Diane said Bobby had his own car, a blue 1967 Ford Fairlane 500 Squire gifted by an uncle, which he only drove sometimes.

He even borrowed Kim’s pale yellow ’67 Impala to take Lori to the prom. But Diane remembers many Saturday nights when he would chauffeur her and her friends to the skating rink in the Ford.

His only condition was that they were ready to go when he was.

Kim had Bobby over for dinner at her Drexel Hill apartment the night before his death. They likely feasted on chicken cutlets, one of Bobby’s favorites.

According to his mother, Bobby had been hired at an auto body shop in Lima not long before his death and was excited about it.

“He was supposed to start Monday, and he died (the previous) Thursday,” Marilyn said.

Bobby was about 17 when he worked for a short time at a body shop owned by former Darby Police Chief Robert Smythe. Smythe retired from the force in 2020 after 50 years, 36 as chief.

“Here was a kid who had a future,” Smythe recently said. “There was no reason for anyone to hurt this kid.”

The knock

The knock

The train conductor called the police about 10:30 p.m. on July 12, 1979.

Some confusion about jurisdiction among neighboring police departments delayed the investigation, ultimately led by then-Darby Police Superintendent Russell Emery and the Delaware County Criminal Investigation Division.

Shortly after 1 a.m. on Friday, July 13, two Darby officers knocked on Marilyn’s front door.

Marilyn, James, Barbara, Larry and Diane had been home briefly from the ballpark and were all upstairs in bed.

A family friend from out of town, who had an early morning flight out of Philadelphia and crashed on the living room couch, opened the door. But Marilyn was just a little behind.

“Is Bobby home?” the officers asked.

“Yeah, he is in bed,” responded Marilyn.

Diane remembers her mother rushing to check Bobby’s bedroom, only to find he wasn’t there.

By then, the officers had left but returned a short time later. This time, they had with them a silver arrowhead pendant — a Sarah Coventry piece Kim had gifted to Bobby — and then asked for a photograph of Bobby. A paramedic at the scene had apparently recognized Bobby.

“What are you trying to say to me,” Marilyn recalled asking the officers at one point, knowing the answer no parent wants to hear.

Kim recalled the panic of being at home miles away and picking up her ringing phone only to hear her mother screaming.

“Mike and I jumped in the car,” she recalled. “My husband and father went to the medical examiner’s office.”

Mike O’Hanlon said they all wanted to believe it was a mistake, that it wasn’t Bobby.

“It wasn’t a mistake,” Mike said.

Lost in grief, Marilyn barely left her rocking chair.

James, Kim and Barbara made Bobby’s funeral arrangements. Some family and a few close friends viewed Bobby before the doors at Marvil Funeral Home opened to the public.

Bobby’s biological father was provided separate time to see his son.

The line of mourners gathered at Marvil’s on Sunday evening, July 15, 1979, stretched along MacDade Boulevard, passing the McDonald’s blocks away.

Bobby’s only suit was green, which he detested, so he was laid out in dress pants, a shirt, and boots in the open casket.

The crowd was just as heavy the following Monday for his Mass at Blessed Virgin Mary Church, the family parish, which was followed by his burial in Holy Cross Cemetery.

It was the same morning Bobby should have been starting his new job.

“God of the living and the dead, may those who faithfully believed in you on Earth praise you forever in the joy of heaven,” Bobby’s memorial prayer card reads in part.

“I just remember a ton of people were crying,” Larry Schad said. “Bobby was a really good guy. I wish I had a friend like him in my adult years.”

A few sentimental things buried with Bobby included his favorite Rod Stewart “Every Picture Tells a Story” album from Kim, and a pack of Parliament cigarettes from Barb so he could still have his occasional smoke in heaven, recalled Diane.

Only a few family members knew that Kim had also put some cash in Bobby’s pants pocket so he would never be broke.

Diane didn’t put anything in the casket, and was even refusing to go to the services until brother-in-law Mike said her parents needed her.

“I was so angry. I didn’t want to see my brother that way, or my parents,” she recalled. “I thought that seeing him would make it real.”

She was right.

Police investigation

Police investigation

After Bobby’s funeral, the focus shifted to the murder investigation.

“There were detectives at the house every day,” Diane said. “They would walk in.”

Kim, who was 21 then, said she would hang on corners, hoping to glean information from other kids. Diane purposely went to parties looking for information from other teens.

In July 1979, Joe Gabe was 9 and looking forward to a fun summer.

A 31-year law enforcement veteran, one of the reasons he became a police officer was to help families like Bobby’s. It’s one of the cases he inherited when he took the reins as chief on Nov. 1, 2020.

A grand jury probe two years after Bobby’s murder resulted in perjury charges against a woman who told investigators she overheard two individuals admit to killing Bobby but later denied the statement, according to newspaper accounts.

Over the years, police efforts to advance the case included trips to Florida and North Carolina to interview witnesses.

Smythe was a Darby patrol officer when Bobby was murdered.

In 2000, as chief, he reopened the case, assigning four detectives to re-interview witnesses and re-examine evidence.

He thought an arrest was imminent.

“One thing I wanted before I retired was to go to Mrs. Dougherty and say, ‘We locked that SOB up,’ but we couldn’t do it,” said Smythe, encouraged at the time by the recovery of the suspected murder weapon, but hindered by what he cited as evidentiary and prosecutorial factors, and the death of a witness.

Name as tribute

All 10 nieces and nephews can tell you everything about their Uncle Bobby.

“We hear about him as if he’s still here,” niece Michelle O’Hanlon McCunney said. “I don’t remember any part of my life without having him in it, even though he was never here.”

When Michelle, an artist like her Uncle Bobby, sketched the faces of all 10 grandchildren — including her twin sister Jamie and brother Michael O’Hanlon; cousins John, Jim and Danny Higgins; and Joe, Michael, Stephen and Robert O’Hara — in a portrait for her grandmother’s birthday two years ago, she encircled them around a favorite image of Uncle Bobby.

“There are a lot of childhood pictures, but the main picture that always stood out to us was his graduation picture,” she said.

Three nephews carry Robert as a middle name: Diane’s eldest son, Michael Robert O’Hara; Kim’s son, Michael Robert O’Hanlon; and Barbara’s son, James Robert Higgins.

Diane’s youngest, Robert James O’Hara, 32, an attorney from Ridley Park, couldn’t be more proud to be his uncle’s namesake.

When Robert O’Hara’s wife, Theresa, gives birth in July to their first child, a son, he will be named Robert James O’Hara Jr., carrying on a legacy of love.

“He will know all the stories about my uncle, his great-uncle,” the dad-in-waiting said.

Marilyn speaks for the whole family when she says love for Bobby is infinite, and hope for justice for Bobby never wanes.

“There is always hope,” the beloved matriarch said.

About this Series

The ‘Remember Me?’ series serves a crucial role in our work. It’s a platform where we share the stories of victims in stalled cases, keeping their memory and the need for justice alive.

One of the most frustrating things to investigators is the empty feeling of incompleteness. Nothing is more gratifying than completing an investigation that appeared impossible.

The Office of the District Attorney has two specific divisions: one that prosecutes criminal matters before the court and the other that conducts investigations to ensure those cases have been brought to their legal and logical conclusion. To complete this process, several elements must be met, including a review of physical and circumstantial evidence, witness and victim accounts of the event, and an attempt to speak with the accused persons.

Many things can hamper or stall any probe. Anything from uncooperative or incapacitated persons to a lack of technological and scientific resources can hinder forwarding a crime to prosecution.

However, the investigators remember these unfinished cases. They are taken to the furthest possible point and then periodically reviewed. When new information, evidence or forensic analysis emerges, cases are pursued with the same vigor as they initially occurred.

I hope that by sharing victims’ stories in some of these stalled cases, the members of law enforcement will be provided with information and evidence that will push the investigation into the hands of the prosecutors.

Today, as part of the occasional “Remember Me?” series, we share our 11th installment, the story of 19-year-old Robert “Bobby” Suny.

With every “Remember Me?” article, including Bobby’s Story, along with the previously published Amanda’s (DeGuio) Story, Dwayne’s (Briscoe Jr.) Story, Robby’s (Payne) Story, Gary’s (Drais) Story, Ryan’s (Ferris) Story, Timothy’s (Hamler) Story, Kyle’s (Haley) Story, Sinsir’s (Parker) Story, Kevin’s (Alvin Jude Carroll) Story and John’s (Kilman) Story, we intend to show that victims will not be forgotten.

Chief James E. Nolan IV

Director Delaware County District Attorney’s Office

Criminal Investigation Division